Direct access versus physician’s pre‑authorized laboratory testing: The experience at a clinical laboratory in South‑South, Nigeria

Main Article Content

Abstract

Background: The traditional health-care model in this country places the physician (or appropriate ordering provider) in control of determining what diagnostic and therapeutic monitoring (including laboratory tests) is to be performed on a patient. A paradigm shift in the way medical care is provided has been observed; with a change in the delivery of health-care moving from physicians into the hands of the patients. One manifestation of this has been direct access testing (DAT) for laboratory services defined as patient (as opposed to physician) initiated testing of human specimens. Appropriateness of tests ordered and reliable interpretation of test results are some of the concerns associated with DAT.

Aim: To determine the comparative evaluation of DAT compared to physicians’ pre-authorised laboratory testing at a clinical laboratory.

Methods: All laboratory requisition orders made to the Pathology Department at Bayelsa Diagnostic Centre, Yenagoa, Bayelsa State within a 2-year period were evaluated.

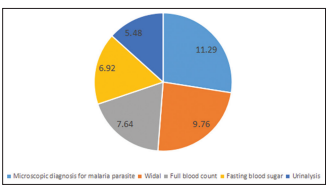

Results: A total of 15,755 requisition orders were analysed. The prevalence of DAT was 21.2% compared to 78.8% of physicians pre-authorised laboratory tests. Nine out of the ten most frequently ordered investigations: full blood count, electrolyte, urea and creatinine, microscopy, culture and sensitivity, microscopic diagnosis of malaria parasite, (urinalysis, Widal test, lipid profile, liver function test

and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were pre-dominantly physicians’ pre-authorised requisition orders. Fasting blood glucose was the only investigation that had a higher prevalence from DAT. More than half (1753 [52.5%]) of the self-referred patients did not present with clinical history while majority (10,087 [81.2%]) with laboratory tests pre-authorised by physicians presented with clinical details.

Conclusion: This study highlights that laboratory test pre-authorised by physicians still remains the traditional healthcare model in South-south Nigeria.

Downloads

Article Details

The journal grants the right to make small numbers of printed copies for their personal non-commercial use under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

1. Ilahi M. What is Direct Access Testing and How Can We Afford It? Health Law Perspective, University of Houston Health Law and Policy Institute; January, 2016. Available from: http://www.law.uh.edu/healthlaw/perspectives/homepage.asp. [Last accessed on 2019 Jul 09].

2. Pitkin F, Watson L, Foster R, Poorman T, Martin A. Direct to Consumer Laboratory Testing: A Review. Annals of Clinical and Laboratory

Research 2017;5:164-6.

3. Direct Access Testing and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) Regulations. Available from: https://www. cms.gov/Regulations‑and‑Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/downloads/directaccesstesting.pdf. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 31].

4. Consumer Access to Laboratory Testing and Information. American Society for Clinical laboratory Science; c2012. Available from: https://www.ascls.org/position‑papers/179‑direct‑access‑testing/155‑direct‑access‑testing. [Last accessed on 2019 Jan 12].

5. Klonoff DC. Benefits and limitations of self‑monitoring of blood glucose. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2007;1:130‑2.

6. O’Kane MJ, Pickup J. Self‑monitoring of blood glucose in diabetes: Is it worth it? Ann Clin Biochem 2009;46:273‑82.

7. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Formulating New Rules to Redesign and Improved Care: Crossing the quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press(US); 2001. p. 3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222277/. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 12].

8. Direct Access Testing. Available from: https://www.midlandhealth. org/main/direct‑access‑testing. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 06].

9. Li M, DiamandisEP, Grenache D, Joyner MJ, Holmes DT, Seccombe R. Direct‑to‑Consumer Testing. Clin Chem 2017;63:635‑41.

10. Schulze M. Direct‑access testing: A state‑by‑state analysis. Lab Med 1999;30:371‑3.

11. Adegoke OA, Idowu AA, Jeje OA. Incomplete laboratory request forms as a contributory factor to preanalytical errors in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Afr J Biochem Res 2011;5:82‑5.

12. Adamu S, Mohammed A, El‑Bashir JM, Abubakar JD, Mshelia DS. Incomplete patient data on chemical pathology laboratory forms in a

tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Ann Trop Pathol 2018;9:47‑9.

13. Nutt L, ZemlinAE, Erasmus RT. Incomplete laboratory request forms: The extent and impact on critical results at a tertiary hospital in South

Africa. Ann Clin Biochem 2008;45:463‑6.

14. Abah AE, Temple B. Prevalence of malaria parasite among asymtomatic primary school children in Angiama community, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Tropical Med Surg 2015;4:203.

15. Madukaku CU, Nosike DI, Nneoma CA. Malaria and its burden among pregnant women in parts of the Niger Delta area of Nigeria. Asian

Pacific J Reproduc 2012;1:147‑51.