Factors responsible for discontinuation of long‑term reversible contraceptives in a tertiary facility in Northeastern Nigeria

Main Article Content

Abstract

Background: The emergence of long-term reversible contraceptives (LARC) has helped in reaffirming the concept of Family Planning (FP) 2020. LARC is one of the safest and most effective methods covering both hormonal implants and intrauterine devices (IUDs). However, despite their acceptability and wide usage, they are associated with undesired effects limiting their use ranging from personal to device-related or both.

Aim: This study is aimed at determining the reasons for the discontinuation of LARCs among women accessing FP services in Bauchi.

Methods: The study was for 1-year period. It was a retrospective survey of 335 clients that presented to the FP unit of a tertiary institution in Northeastern Nigeria for removal of implants. Data were inputted into and analysed using SPSS version 21 and results presented in tables and charts.

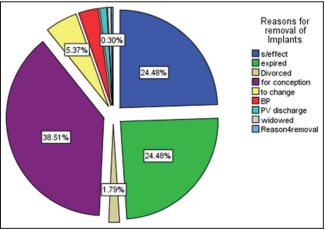

Results: A total of 1069 clients had one method of contraception or the other over the study periods. About 335 (31.3%) clients had removal of LARCs (53.4%, 18.2% and 28.4%, for Implanon, Jadelle and IUDs, respectively). The mean parities of the clients were 3 +_ 0.55. The most common indications for removal of implants observed in the study included, the desire for pregnancy (38.5%), expired implants and untolerable side effects (24.5%) each.

Conclusions: LARCs were the most common form of contraceptives used by women during the study period. The most common reason for removal of LARCs implants discovered was for feature pregnancy, undesired effects and implants expiry.

Downloads

Article Details

The journal grants the right to make small numbers of printed copies for their personal non-commercial use under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

1. Joshi R, Khadilkar S, Patel M. Global trends in use of long‑acting reversible and permanent methods of contraception: Seeking a balance. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131(Suppl 1):S60‑3.

2. Curry DW, Rattan J, Huang S, Noznesky E. Delivering high‑quality family planning services in crisis‑affected settings II: Results. Glob Health Sci Pract 2015;3:25‑33.

3. Charyeva Z, Oguntunde O, Orobaton N, Otolorin E, Inuwa F, Alalade O, et al. Task shifting provision of contraceptive implants to community health extension workers: Results of operations research in Northern Nigeria. Glob Health Sci Pract 2015;3:382‑94.

4. Ngo TD, Nuccio O, Pereira SK, Footman K, Reiss K. Evaluating a LARC expansion program in 14 sub‑Saharan African countries: A service delivery model for meeting FP2020 goals. Matern Child Health J 2017;21:1734‑43.

5. Christofield M, Lacoste M. Accessible contraceptive implant removal services: An essential element of quality service delivery and scale‑up.

Glob Health Sci Pract 2016;4:366‑72.

6. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International. National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International, 2014; 127‑54.

7. Wickstrom J, Jacobstein R. Contraceptive security: Incomplete without long‑acting and permanent methods of family planning. Stud Fam

Plann 2011;42:291‑8.

8. Kalra N, Ayankola J, Babalola S. Healthcare provider interaction and other predictors of long‑acting reversible contraception adoption among women in Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;144:153‑60.

9. Mohammed-Durosinlorun A, Adze J, Bature S, Abubakar A, Mohammed C, Taingson M, et al. Uptake and Predictors of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives among Women in a Tertiary Health Facility in Northern Nigeria. Journal of Basic and Clinical Reproductive Sciences. 2017;6.

10. Eke AC, Alabi‑Isama L. Long‑acting reversible contraception (LARC) use among adolescent females in secondary institutions in Nnewi, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;31:164‑8.

11. Benova L, Cleland J, Daniele MA, Ali M. Expanding method choice in Africa with long‑acting methods: IUDs, implants or both? Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2017;43:183‑91.

12. Federal Ministry of Health [Nigeria]. Task‑shifting and task‑sharing policy for essential health care services in Nigeria. Abuja (Nigeria): Federal Ministry of Health; 2014.

13. Family Planning 2020 (FP2020). FP2020 Measurement Annex: November 2015. Washington (DC): United Nations Foundation, 2015. Available from: http://progress.familyplanning2020.org/uploads/03/00/FP2020_MeasurementAnnex_2015. [Last accessed 2018 Nov 21].

14. Kenya Health Information System (Kenya DHIS2). Nairobi (Kenya): Kenya Ministry of Health. Available from: https://hiskenya.org/dhis‑web‑commons/security/login.action. [Last accessed on 2019 Jan 01].

15. Mrwebi KP, Goon DT, Owolabi EO, Adeniyi OV, Seekoe E, Ajayi AI. Reasons for discontinuation of implanon among users in buffalo city

metropolitan municipality, South Africa: A cross‑sectional study. Afr J Reprod Health 2018;22:113‑9.

16. Adeagbo O, Mullick S, Pillay D, Chersich M, Morroni C, Naidoo N, et al. Uptake and early removals of implanon NXT in South Africa: Perceptions and attitudes of healthcare workers. S Afr Med J 2017;107:822‑6.

17. Birhane KA, Hagos SE, Fantahun ME. Early discontinuation of implanon and its associated factors among women who ever used implanon in Ofla district, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2015; 6:544‑51.

18. Chigbu B, Onwere S, Onwere A, Kamanu C, Chigbu E. Pattern of Discontinuation of Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives in Southeastern Nigeria [9N]. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016;127:116S.

19. Ezegwui HU, Ikeako LC, Ishiekwene CI, Oguanua TC. The discontinuation rate and reasons for discontinuation of implanon at the family planning clinic of University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) Enugu, Nigeria. Niger J Med 2011;20:448‑50.

20. Performance, Monitoring and Accountability 2020 (PMA2020) Project, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife and Bayero University. Kano,

Nigeria, Baltimore, MD: PMA2020, Bill & Melinda Gates Institute for Population and Reproductive Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2016.

21. Pam VC, Mutihir JT, Nyango DD, Shambe I, Egbodo CO, Karshima JA, et al. Sociodemographic profiles and use‑dynamics of jadelle (levonorgestrel) implants in Jos, Nigeria. Niger Med J 2016;57:314‑9.

22. Bolarinwa OA, Olagunju OS. Knowledge and factors influencing long acting reversible contraceptive use among women of reproductive age

in Nigeria. Gates Open Res 2019;14:3.

23. Garbers S, Haines‑Stephan J, Lipton Y, Meserve A, Spieler L, Chiasson MA. Continuation of copper‑containing intrauterine devices at 6 months. Contraception 2013;87:101‑6.

24. Dickerson LM, DiazVA, Jordon J, Davis E, Chirina S, Goddard JA, et al. Satisfaction, early removal, and side effects associated with long‑acting

reversible contraception. Fam Med 2013;45:701‑7.

25. Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, Mete M, Nelson CB, Gomez‑Lobo V. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:585‑92.

26. Elias B, Hailemariam T. Implants contraceptive utilization and factors associated among married women in the reproductive age group (18-49 year) in Southern Ethiopia. J Womens Health Care 2015;4:281‑7.

27. Gudaynhe SW, Zegeye DT, Asmamaw T, Kibret GD. Factors affecting the use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods among married

women in Debre Markos town, Northwest Ethiopia 2013. Glob J Med Res 2014;14:8‑15.

28. Vogel JP, Pileggi‑Castro C, Chandra‑Mouli V, Pileggi VN, Souza JP, Chou D, et al. Millennium development goal 5 and adolescents: Looking back, moving forward. Arch Dis Child 2015;100(Suppl 1):S43‑7.

29. Azmoude E, Behnam H, Barati-Far S, Aradmehr M. Factors affecting the use of long-acting and permanent contraceptive methods among

married women of reproductive age in East of Iran. Women's Health Bulletin 2017;4.

30. Coombe J, Harris ML, Loxton D. Who uses long‑acting reversible contraception? Profile of LARC users in the CUPID cohort. Sex Reprod Healthc 2017;11:19‑24.

31. White K, Hopkins K, PotterJE, Grossman D. Knowledge and attitudes about long‑acting reversible contraception among Latina women who

desire sterilization. Womens Health Issues 2013;23:e257‑63.