Blood pressure, blood sugar and gingival crevicular fluid volume in adult females with malocclusion in Benin City, Nigeria

Main Article Content

Abstract

Background: The gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) may be a valuable adjunct in the initial diagnosis and assessment of the severity of periodontal disease in patients with hypertension and diabetes. The GCF volume may be used to monitor and plan appropriate dental treatment and prevent progression of disease in adult patients with malocclusion who have hypertension or diabetes.

Aim: The aim of this study is to determine the volume and correlation between blood pressure, blood sugar and GCF volume in adult females with malocclusion in Benin City, Nigeria.

Methods: A total of 152 fasting women aged 26–65 years were divided into two groups as follows: Group 1: Malocclusion; n = 82 (54%) (crowding - 41, spacing – 39 and anterior open bite - 2) and Group 2: Normal occlusion; n = 70 (46%). Blood pressure and blood sugar values were obtained and the GCF volume measured. Correlations between age, gender, probing depth, malocclusion, blood pressure, blood sugar and GCF volume were determined using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 16) software. Significant values of P < 0.05 were applied.

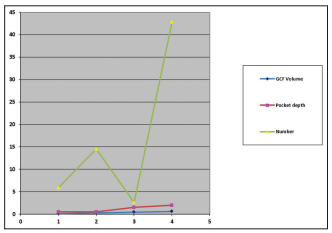

Results: The highest GCF volume in the total sample studied was 2.17 µL in 1.3% and the most prevalent was seen in 0.62 µL in 42.8%. GCF volumes of 0.93 µL were most prevalent in crowding in 14.6% and in 0.62 µL in spacing in 9.9%. Furthermore, a GCF volume of 0.62 µL was highest in blood pressure of 121/89 mmHg in 9.9% and blood sugar levels of 80–120 mg/dl in 25% of subjects, respectively. Malocclusion (crowding, spacing and anterior open bite) exhibited a higher number 45.1% in GCF volume of 0.62 µL. There was, however, no significant relationship between blood pressure, blood sugar and GCF volume (P > 0.05) in both the malocclusion and control groups. There was also a statistically significant difference between GCF volume and pocket depth (P < 0.01).

Conclusion: This study revealed that blood pressure and blood sugar levels in adult females with malocclusion do not affect GCF volume. A positive correlation, however, exists between GCF volume, pocket depth and oral hygiene in Benin City.

Downloads

Article Details

The journal grants the right to make small numbers of printed copies for their personal non-commercial use under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

1. Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology. 11th ed. St Loius Missouri: Elseiver Saunders;2012:263-6.

2. Brill N, Krass B. The passage of tissue fluid into the clinically healthy gingival pocket. Acta Odontol Scand 1958;16:223‑45.

3. Goodson JM. Gingival crevice fluid flow. Periodontology 2000 2003;31:43‑54.

4. Brill N. The gingival pocket fluid studies of its occurrence, composition and effects. Acta Odontol Scand 1959;20(Suppl 32):32.

5. Pashley DH. A mechanistic analysis of gingival fluid production. J Periodontal Res 1976;11:121‑34.

6. Golub LM, Kleinberg I. Gingival crevicular fluid: A new diagnostic aid in managing the periodontal patient. Oral Sci Rev 1976;8:49‑61.

7. Miller J, Hobson P. The relationship between malocclusion, oral cleanliness, gingival conditions and dental caries in school children. Br Dent J 1961;111:43‑52.

8. Bollen AM. Effects of malocclusions and orthodontics on periodontal health: Evidence from a systematic review. J Dent Educ 2008;72:912‑8.

9. Onyeaso CO, Arowojolu MO, Taiwo JO. Oral hygiene status and occlusal characteristics of orthodontic patients at University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Odontostomatol Trop 2003;26:24‑8.

10. Abdulwahab B. Lower arch crowding in relation to periodontal disease. MDJ 2008;5:154‑8.

11. Richardson ME. Late lower arch crowding in relation to primary crowding. Angle Orthod 1982;52:300‑12.

12. Ize‑Iyamu IN. Prevalence of retained primary teeth among children with anterior arch crowding in Benin City, Nigeria. Ann Biomed Sci 2011; 10:21‑8.

13. Diedrich P1. Periodontal relevance of anterior crowding. J Orofac Orthop 2000;61:69‑79.

14. Al‑Jubory HA. Gingival fluid status in improperly restored and non‑restored teeth. J Coll Dent 2005;17:77‑9.

15. Fitzsimmons TR, Sanders AE, Bartold PM, Slade GD. Local and systemic biomarkers in gingival crevicular fluid increase odds of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2010;37:30‑6.

16. Marchetti E, Monaco A, Procaccini L, Mummolo S, Tete S, Baldini A, et al. Periodontal disease: The influence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr

Metab 2012;9:4‑10.

17. Cakic S. Gingival crevicular fluid in the diagnosis of periodontal and systemic diseases. Srp Arh Celok Lek 2009;137:298‑303.

18. Lamster IB, Ahlo JK. Analysis of gingival crevicular fluid as applied to the diagnosis of oral and systemic diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1098:216‑29.

19. Ellis JS, Seymour RA, Monkman SC, Idle JR. Gingival sequestration of nifedipine in nifedipine‑induced gingival overgrowth. Lancet 1992; 339:1382‑3.

20. Monkman SC, Ellis JS, Cholerton S, Thomason JM, Seymour RA, Idle JR. Automated gas chromatographic assay for amlodipine in plasma and gingival crevicular fluid. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl 1996;678:360‑4.

21. Ellis JS, Seymour RA, Monkman S, Idle JR. Disposition of nifedipine in plasma and gingival crevicular fluid in relation to drug‑induced gingival overgrowth. J Periodontal Res 1993;28:373‑8.

22. Ranney RR, Montgomery EH. Vascular leakage resulting from topical application of endotoxin to the gingiva of the beagle dog. Arch Oral

Biol 1973;18:963‑70.

23. Loe H, Holm‑Pedersen P. Absence and presence of fluid from normal and inflamed gingivae. Periodontics 1965;3:171‑7.

24. Söderholm G, Atiström R. Vascular permeability during initial gingivitis in dogs. J Periodontal Res 1977;12:395‑401.

25. Sueda T, Bang J, Cimasoni G. Collection of gingival fluid for quantitative analysis. J Dent Res 1969;48:159.

26. Cimasoni G, Giannopoulou C. Can Crevicular Fluid Component Analysis Assist in Diagnosis and Monitoring Periodontal Breakdown?

Periodontology Today, International Congress. Zurich, Basel: Karger, 1988; 260‑70.

27. Kaslick RS, ChasensAI, MandelID, Weinstein D, Waldman R, Pluhar T, et al. Quantitative analysis of sodium, potassium and calcium in gingival

fluid from gingiva in varying degrees of inflammation. J Periodontol 1970;41:93‑7.

28. Koregol AC, More SP, Nainegali S, Kalburgi N, Verma S. Analysis of inorganic ions in gingival crevicular fluid as indicators of periodontal

disease activity: A clinico‑biochemical study. Contemp Clin Dent 2011;2:278‑82.

29. Skapski H, Lehner T. A crevicular washing method for investigating immune components of crevicular fluid in man. J Periodontal Res 1976; 11:19‑24.

30. Griffiths GS, Sterne JA, Wilton JM, Eaton KA, Johnson NW. Associations between volume and flow rate of gingival crevicular fluid and clinical assessments of gingival inflammation in a population of British male adolescents. J Clin Periodontol 1992;19:464‑70.

31. Challacombe SJ, Russell MW, Hawkes JE, Bergmeier LA, Lehner T. Passage of immunoglobulins from plasma to the oral cavity in rhesus

monkeys. Immunology 1978;35:923‑31.

32. Rody WJ Jr., Wijegunasingbe M, Wiltshire WA, Dufault B. Differences in the gingival crevicular fluid comparison between adults and

adolescents undergoing orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 2014;84;120-6.

33. Lamster IB, Harper DS, Goldstein S, Celenti RS, Oshrain RL. The effect of sequential sampling on crevicular fluid volume and enzyme

activity. J Clin Periodontol 1989;16:252‑8.

34. Tymkiw KD. The Influence of Smoking on Cytokines in the Gingival Crevicular Fluid in Patients with Periodontal Disease. Thesis University of Iowa; 2008. Available from: http://www.ir.uiowa.edu/etd/26. [Last accessed 2016 May 14].

35. Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc 1964;68:7‑13.

36. Rivas‑Tumanyan S, Spiegelman D, Curhan GC, Forman JP, Joshipura KJ. Periodontal disease and incidence of hypertension among older adults in Puerto Rico. J Periodontol 2012;25:770‑6.

37. Ellis JS, Seymour RA, Thomason JM, Butler TJ, Idle JR. Periodontal variables affecting nifedipine sequestration in gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontal Res 1995;30:272‑6.

38. Marchetti E, Monaco A, Procaccini L, Mummolo S, Gatto R, Tetè S, et al. Periodontal disease: The influence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012;9:88.

39. Umoh AO, Ojehanon PI, Savage KO. Effect of maternal periodontal status on birth weight. Eur J Dent 2013;2:158‑62.

40. Gomes SC, Piccinin FB, Oppermann RV, Susin C, Marcantonio RA. The effect of smoking on gingival crevicular fluid volume during the

treatment of gingivitis. Acta Odontol Latinoam 2009;22:201‑6.